Edith Collier: Early New Zealand Modernist

- NZ Booklovers

- Sep 10, 2024

- 5 min read

This thorough and thought-provoking book will ignite interest in the life and works of New Zealand artist Edith Collier, who is now recognised as one of New Zealand’s early modernist painters. Most of Collier’s works are held by Te Whare o Rehua Sarjeant Gallery (the Sarjeant) in Whanganui. An exhibition celebrating Collier’s works will be held to coincide with the opening of the restored Sarjeant in November 2024.

Over 450 of Collier’s works are in the care of the Sarjeant and many of these works feature in the book. Outside the Sarjeant, very few of Collier’s works are in public collections. Many still belong to members of her extended family. Collier’s family continue to be actively involved in maintaining her legacy through their ongoing partnership with the Serjeant.

In one of the first sections of the book, writer and curator Jill Trevelyan introduces Collier the painter and Collier the person. The following five chapters focus on areas where Collier lived, studied, and worked: Whanganui, England and Ireland, London, St Ives, and Kāwhia. In each place, she learned how to capture the differing light, terrain, weather, and other characteristics unique to the region. She often developed strong relationships with locals, including those whose portraits she painted.

Over 20 contributors from diverse backgrounds provide their perspectives on the work Collier produced during the time she spent in each area. These include essays from contemporary artists, art historians and curators, academics, writers and poets. Collier’s friendships with her mentors, teachers and fellow artists are often mentioned. The contributors also offer insights into the evolution of Collier’s style, taking into account social and political influences (including the effects of the First World War), and Collier’s exposure to the European avant-garde and Japanese art. Within this section Gregory O’Brien carefully analyses Boy with Noah’s Ark, noting an affinity with the “folk and illustrative arts of the period”. He draws attention to specific components:

Collier has packed the composition with lively details; positive and negative shapes are slotted together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. … If the composition has some degree of turbulence in its zig-zag pattern and intensity, the result is whimsical rather than apocalyptic. Both painter and subject – and, in turn, viewer – revel in the brightness and immediacy of this benign, make-believe deluge, this feast of colours and shapes.

Collier’s connection to Kāwhia, where she painted several portraits of Māori elders as well as landscapes, continues to be honoured. In 2023 a series of hui held at Maketuu Marae united local Māori, Collier family members, a team from the Sarjeant Gallery, and others with an interest in Collier’s art. Together they explored and celebrated Collier’s links to the land and the people who lived there. (The book includes a transcript of the hui koorero.) One of the women Collier painted was kuia Tiro Tiro Ponui, whose great-granddaughter shares the whakapapa of her tīpuna in the book. She often visits her great-grandmother’s portrait when it is exhibited at the Sarjeant:

I … gaze deep into her eyes – is part of her spirit retained in that beautiful painting?

Collier is also held in high regard in Bonmahon, Ireland, where her art captured the history of the small village and the village people.

In the final chapter, several contributors explore Collier’s legacy and influence. Her nephew recalls Aunt Edith’s visits to the family farm and how she sketched Mt Ruapehu during a family outing. He describes the impact of her Breakfast Table oil painting on his own work as a garden designer:

That painting has taught me so much about design… The way the objects are arranged, the repetition of certain colours, the importance of the space at the centre – that empty space is so important.

Collier continues to influence other artists. During the past decade three artists-in-residence at the Sarjeant, all women, have created their own works across varied media inspired by – and responding to – Collier’s practice.

The images throughout the book show that Collier experimented with many different media, producing oil paintings, watercolours, etchings, monoprints, and works in charcoal, pencil, pen and ink. Close-ups of several works provide further insights into Collier’s techniques, with shading and brushstrokes clearly visible. As well as artworks, the book includes other images reflecting Collier’s life and times – such as family photos, excerpts from her letters and postcards, and early photos of Whanganui. The book also presents works by several of Collier’s contemporaries, teachers and friends, including Australian painter Margaret Preston (formerly McPherson) and Dunedin-born Frances Hodgkins.

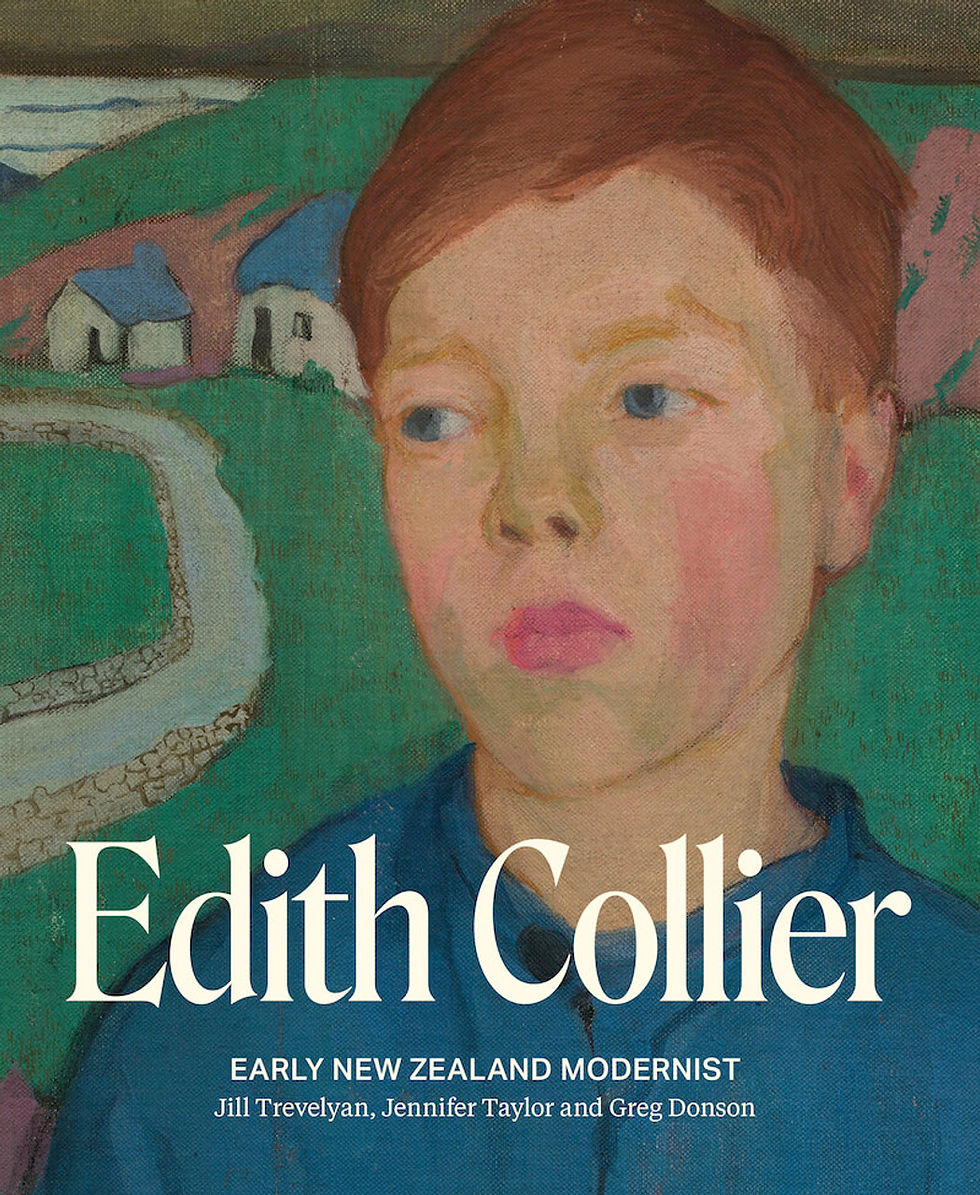

The haunting cover image, Boy Against Landscape, is an excellent example of Collier’s skill in engaging the viewer. Does the red-headed boy’s expression indicate indifference, caution, disappointment, or perhaps boredom from holding a pose? Did he live in one of the coastal cottages depicted in the background, walk along the lane bordered by the stone wall?

A particular strength of the book is the detailed contextual information about the many factors – financial, cultural, geographical, and sociological – that supported or hampered Collier’s development as an artist. Collier was fortunate to have parents who paid her expenses for many years while she was living and studying abroad. Yet she did not live up to her parent’s expectations and there was little commercial return on their investment during their lifetime. Eventually Collier’s parents insisted that she return home. Back in New Zealand she soon took on family caregiving responsibilities. Far from the art scene in Europe, she was now geographically and culturally isolated, time-poor, and plagued by self-doubt. A local critic scorned her work. Her father – in a fit of pique – burned several of Collier’s nude works in a bonfire. (Some that escaped his wrath are included in the book.) Despite setbacks, Collier continued to take part in occasional exhibits and attracted praise and support from some quarters. Over time, however, she lost her confidence, energy and enthusiasm and became increasingly reluctant to part with her work outside the family circle. The authors observe that artists such as Rita Angus, Rata Lovell-Smith, Toss Woollaston and Colin McCahon “would have found Edith’s modernist work … to be of considerable interest, but they had no opportunity to see it”. Collier apparently remained hopeful that she would one day resume painting, but this did not happen before she died at age 79.

The authors encourage consideration of “the way women negotiate the competing demands of artistic and family commitments”. They suggest that Collier’s story has many “what ifs” and raise questions about what Collier may have been able to achieve under different circumstances, whether her talent was wasted, and the extent to which the career of the “modest and publicity-shy” Collier was constrained by her own insecurities as well as by family obligations. They emphasise that “we should not underestimate her courage and agency in achieving as much as she did”.

Poet Airini Beautrais offers her interpretation of Collier’s The Bathers. I love this line from Beautrais’ poem:

I store you, on this cloth, against decay.

For this is what Collier has done, stored objects and people – the cottages and kitchens, landscapes and villages, the Peasant Woman, the Man with Red Cheeks, the girls and schoolboys, and many other subjects – against decay, so that current and future generations can appreciate and contemplate her body of work.

In his foreword, Andrew Clifford, director of the Sarjeant, expresses his hope that the book (along with the upcoming exhibition) “will draw more attention to Edith Collier’s work, increase our understanding of her practice, and contribute further to the significant reputation she deserves”. The book succeeds on all counts.

Reviewer: Anne Kerslake Hendricks

Massey University Press